Source: Jacques-Louis David / Public domain

Inquiry Question: Did Napoleon Bonaparte end the French Revolution?

A. Biography: Who was Napoleon Bonaparte?

Napoleon Bonaparte was born on the island of Corsica in 1769 to an Italian family that was given French noble status nine years later. He attended France’s prestigious Ecole Militaire and was serving in the army when the French Revolution started. He rose quickly to general, gaining fame and power as he won victory after victory. In 1799, he led a coup d’état and was appointed First Consul; within a few years he named himself Emperor and set out to claim an empire.

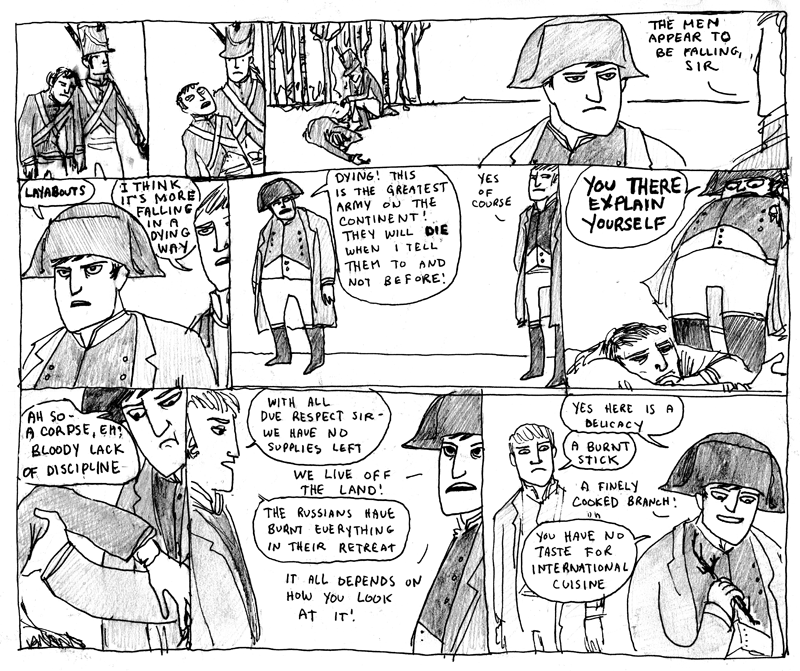

Over the next ten years, the armies of France under his command fought almost every European power, and acquired control of most of continental Europe by conquest or alliance. The disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812 marked a turning point. The defeat at the Battle of Leipzig the next year was the death knell for the Emperor, and he abdicated the next April after the Allied Coalition invaded France.

He was sent in exile to the island of Elba. The next year, he escaped from Elba and marched on Paris, collecting an army as he went. This brief return to power is known as the Hundred Days, but ended definitively with the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815. He spent the rest of his life in exile on the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821.

B. Timeline: What did he do?

| 1796-97 | Italian Campaign. Napoleon took over the French “Army of Italy,” drove the Austrians and Sardinians out of Piedmont, defeated the Papal States, and occupied Venice. This was his first major victory. |

| November 1799 | Coup d’état that established Napoleon as First Consul of France, part of a triumvirate that included Cambacérès and Lebrun. Although the plan was for the three to have equal power, Napoleon quickly became the most powerful. |

| May 1804 | Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor following a national vote. Around 99.3% of all those who participated voted for Napoleon to become Emperor of the French. |

| 1805 | Battle of Austerlitz, where Napoleon defeated the Third Coalition (actually the first coalition mounted against him, rather than against the Revolutionary troops.) Generally viewed as one of his most brilliant battles, the Battle of Austerlitz was fought in what is now the Czech Republic, with Napoleon trouncing the armies of the Austrian and Russian Empires. |

| July 1807 | Treaty of Tilsit. After the battle of Friedland, where Napoleon defeated the Russians, Alexander of Russia negotiated this treaty that would bring peace to Russia. They met on a raft in the middle of the Niemen River to sign the treaty, which had both a public and a private part. In the public part, Russia ceded 50% of Prussian territory to France; in the private part, Alexander agreed that if the British continued the war against France, Russia would join the Continental System of blockades whose goal it was to isolate Britain economically. The result of the treaty was a major realignment of alliances. |

| 1812 | Russian Campaign. Napoleon amassed a huge army and marched to Moscow, not recognizing the challenges of supplying a large army such a long way from home. As the Russian army retreated, they applied a “scorched earth” policy, destroying or carrying off anything that might be useful. As they retreated from Moscow, they set it on fire. Napoleon had counted on billeting his troops in the city during the long Russian winter, but no shelter was left standing. As a result, the French army suffered terribly from starvation and cold as they made the long trip back towards France. |

| October 1813 | German Campaign. Napoleon’s army regrouped in German territory, and battled the Coalition successfully in several locations before suffering a decisive defeat in the Battle of the Nations (Leipzig) at the hands of Germany’s General Blucher. |

| April 1814 | Napoleon abdicated as emperor, and was sent into exile on the Mediterranean island of Elba. He was given “sovereignty” over the island, and actually had his own navy. |

| Sept 1814 to June 1815 | The Congress of Vienna was a lengthy conference between ambassadors from the major powers in Europe. Its purpose was to redraw the political map of Europe following the defeat of Napoleon. The Congress continued in spite of Napoleon’s escape from Elba. |

| February 1815 | Napoleon escaped from Elba, landing in southern France and marching towards Paris, gathering an army around him as he went. |

| June 1, 1815 | The Champ-de-Mai parade and ceremony in Paris reaffirmed Napoleon as Emperor and forced everyone to swear allegiance to him and to the Acte Additional. The Acte was a set of small reforms that disappointed his supporters, to whom he had promised a less dictatorial government. |

| June 18, 1815 | Losing support at home, Napoleon turned to the battlefield where he faced the largest Coalition army yet. His forces were defeated at the Battle of Waterloo, and he escaped to Fontainebleau. |

| June 22, 1815 | Napoleon abdicated a second time, and attempted to escape to the United States. He was captured by the British and eventually transported to the island of St. Helena, where he remained for the rest of his life. |

| 1821 | Napoleon died on St. Helena |

C. Map: Napoleon’s Empire

D. Napoleon and the Revolution: The Napoleonic Code

- As emperor, Napoleon created a new set of laws for France, called the Napoleonic Code.

- This code gave equal rights under the law to all French citizens.

- In other words, everyone in France had to follow the same laws and received the same punishments for breaking them.

- People could only be punished by laws if they were aware of them and could not be punished for breaking a law that did not yet exist (ex post facto).

- Serfdom and feudalism were abolished. The nobility could not continue collecting rents and services from the peasants.

- Religious toleration was guaranteed. In a separate law (Concordant of 1801) the Catholic Church was recognized as the main religion of France, but other religions were permitted.

- More importantly, Napoleon’s code was enforced throughout the French Empire and its dependencies, including Spain, Germany, Italy, and the Low Countries (Belgium and Holland).

E. Primary Source: Napoleon’s Proclamation to His Troops in Italy (March-April 1796)

Friends, I promise you this conquest; but there is one condition you must swear to fulfill—to respect the people whom you liberate, to repress the horrible pillaging committed by scoundrels incited by our enemies. Otherwise you would not be the liberators of the people; you would be their scourge…. Plunderers will be shot without mercy; already, several have been”

“Peoples of Italy, the French army comes to break your chains; the French people is the friend of all peoples; approach it with confidence; your property, your religion, and your customs will be respected.”

“We are waging war as generous enemies, and we wish only to crush the tyrants who enslave you.

F. Primary Source: The Imperial Catechism (1806)

[Background: The catechism was created by Napoleon and taught to the French people in Church by the Catholic clergy. Throughout France, these words were read to the common people]

Question: What are the duties of Christians toward those who govern them, and what in particular are our duties towards Napoleon I, our emperor?

Answer: Christians owe to the princes who govern them, and we in particular owe to Napoleon I, our emperor, love, respect, obedience, fidelity, military service, and the taxes levied for the preservation and defense of the empire and of his throne. We also owe him fervent prayers for his safety and for the spiritual and temporal prosperity of the state.

Question: Why are we subject to all these duties toward our emperor?

Answer: First, because God, who has created empires and distributes them according to his will, has, by loading our emperor with gifts both in peace and in war, established him as our sovereign and made him the agent of his power and his image upon earth. To honor and serve our emperor is therefore to honor and serve God himself. Secondly, because our Lord Jesus Christ himself, both by his teaching and his example, has taught us what we owe to our sovereign. Even at his very birth he obeyed the edict of Caesar Augustus; he paid the established tax; and while he commanded us to render to God those things which belong to God, he also commanded us to render unto Caesar those things which are Caesar’s.

Question: Are there not special motives which should attach us more closely to Napoleon I, our emperor?

Answer: Yes, for it is he whom God has raised up in trying times to re-establish the public worship of the holy religion of our fathers and to be its protector; he has re-established and preserved public order by his profound and active wisdom; he defends the state by his mighty arm; he has become the anointed of the Lord by the consecration which he has received from the sovereign pontiff, head of the Church universal.

Question: What must we think of those who are wanting in their duties toward our emperor?

Answer: According to the apostle Paul, they are resisting the order established by God himself and render themselves worthy of eternal damnation.

“I found the crown of France lying in the gutter, and I picked it up with my sword.”

– Napoleon Bonaparte